This project started from a simple frustration: SWE-Bench only tells you pass/fail. For agentic systems, that’s barely a debugging signal. I wanted to know:

Given a reasonably strong model, where exactly does a coding agent fall apart?

To answer that, I:

- Built a DSPy-based coding agent around Qwen3-Coder-30B-A3B.

- Wrapped SWE-Bench-Lite tasks in a controllable environment (local Docker).

- Logged full execution traces of each run.

- Ran those traces through Docent, using an LLM judge with a custom rubric to tag behaviors and failure modes.

- Quantified how often each failure mode appears and how strongly certain behaviors correlate with success.

1. Experimental Setup

1.1 Benchmark and Compute

- Dataset: 150 randomly sampled tasks from SWE-Bench-Lite.

- Environment: Local Docker, one repo per task; the agent interacts via tools that:

- Read files and diffs

- Search the codebase

- Apply patches

- Run test suites

Because everything ran on my laptop, I constrained:

- Max number of tool calls per issue

- Timeouts for long-running tests or infinite loops

1.2 Model & Baseline Performance

- Model: Qwen/Qwen3-Coder-30B-A3B-Instruct via OpenRouter

- Framework: DSPy for agent programming

On my DSPy agent:

- Resolve rate: 59/150 tasks (39.3%)

For context (same model, different scaffolding):

- Mini-SWE-Agent: ~37.7%

- OpenHands scaffolding (Qwen3-Coder-30B-A3B, 500 steps): 51.6%

So the model is clearly capable of >50% with stronger scaffolding. The 30% I observed is not a model ceiling; it’s an agent design problem, which makes the trace analysis interesting rather than depressing.

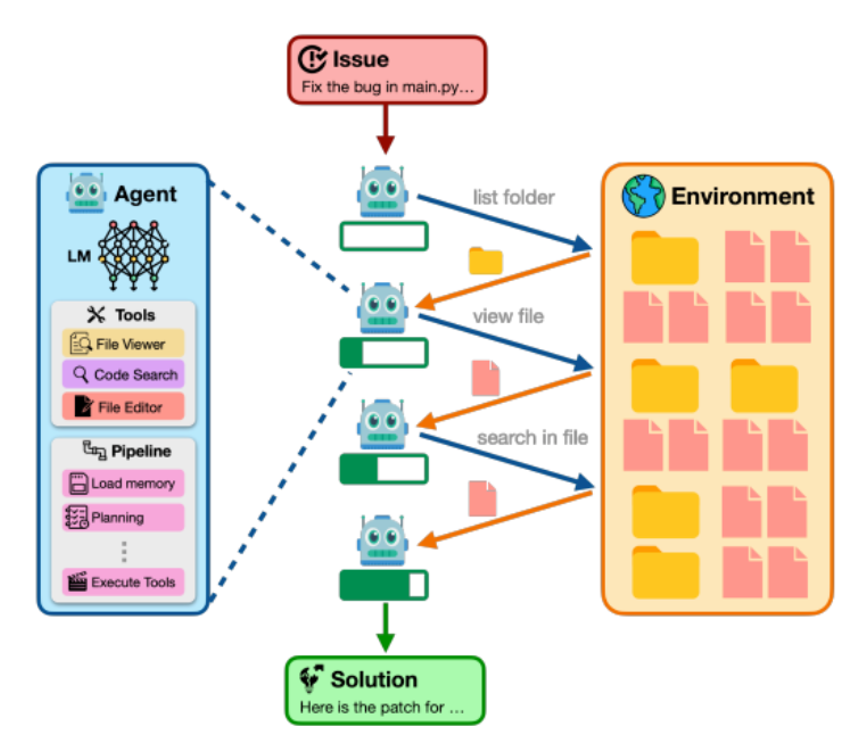

2. DSPy Agent Design

The core of the project is a programmable DSPy “program” that turns SWE-Bench tasks into a multi-step tool-using process.

2.1 Environment Abstraction

Each SWE-Bench task is wrapped as an environment with the following primitives:

get_problem_description()read_file(path)search_codebase(query)apply_patch(diff)run_tests()→ returns test output + pass/failget_repo_state()→ metadata / current diff summary

These are exposed to the LLM as tools; DSPy handles how the language model calls them.

2.2 DSPy Program Structure

At a high level, my agent loop looks like this:

state = {

"issue": issue_text,

"repo_summary": initial_repo_summary,

"history": [],

}

for step in range(MAX_STEPS):

thought = lm.decide_next_action(state) # DSPy module

tool_call = decode_tool_call(thought)

tool_result = env.execute(tool_call)

state["history"].append({

"thought": thought,

"tool_call": tool_call,

"result": tool_result,

})

if tool_call.name == "run_tests" and tool_result.tests_passed:

breakIn DSPy terms, this is implemented as a sequence of modules:

-

Planning / subgoal selection

- A module that takes (issue, history) and outputs a short “next action plan” + candidate tool.

-

Tool-calling / arguments module

- Takes the plan and emits a structured tool call (e.g.,

search_codebase("XYZ"),read_file("foo.py"),apply_patch(diff)).

- Takes the plan and emits a structured tool call (e.g.,

-

Patch synthesis module

- When enough context is gathered, a specialized module proposes a patch diff conditioned on:

- Issue description

- Relevant files

- Previous attempts and test outputs

- When enough context is gathered, a specialized module proposes a patch diff conditioned on:

-

Termination heuristic

- If tests pass → success

- If model repeatedly cycles with no new information → forced stop

DSPy’s advantage here is that each module is typed and interpretable: for every call I know which module ran, what its inputs were, and what it output. That structure is exactly what I log into traces.

3. Logging and Trace Collection

For every task, I emit a structured trace:

{

"task_id": "...",

"status": "success" | "fail",

"steps": [

{

"step_idx": 0,

"module": "Planner",

"thought": "... natural language plan ...",

"tool_call": {"name": "search_codebase", "args": {"query": "..." }},

"tool_output": "... snippet or test output ...",

},

...

],

"final_patch": "... unified diff ...",

"test_log": "... full test output ..."

}All runs are written to JSONL, giving me:

- Complete module-level behavior

- Full tool call sequence

- All model thoughts and self-talk

- Final success/fail label from SWE-Bench

This becomes the raw material for Docent + LLM-judge evaluation.

4. Log Analysis with Docent and Rubric-Based LLM Judging

4.1 Designing the Rubric

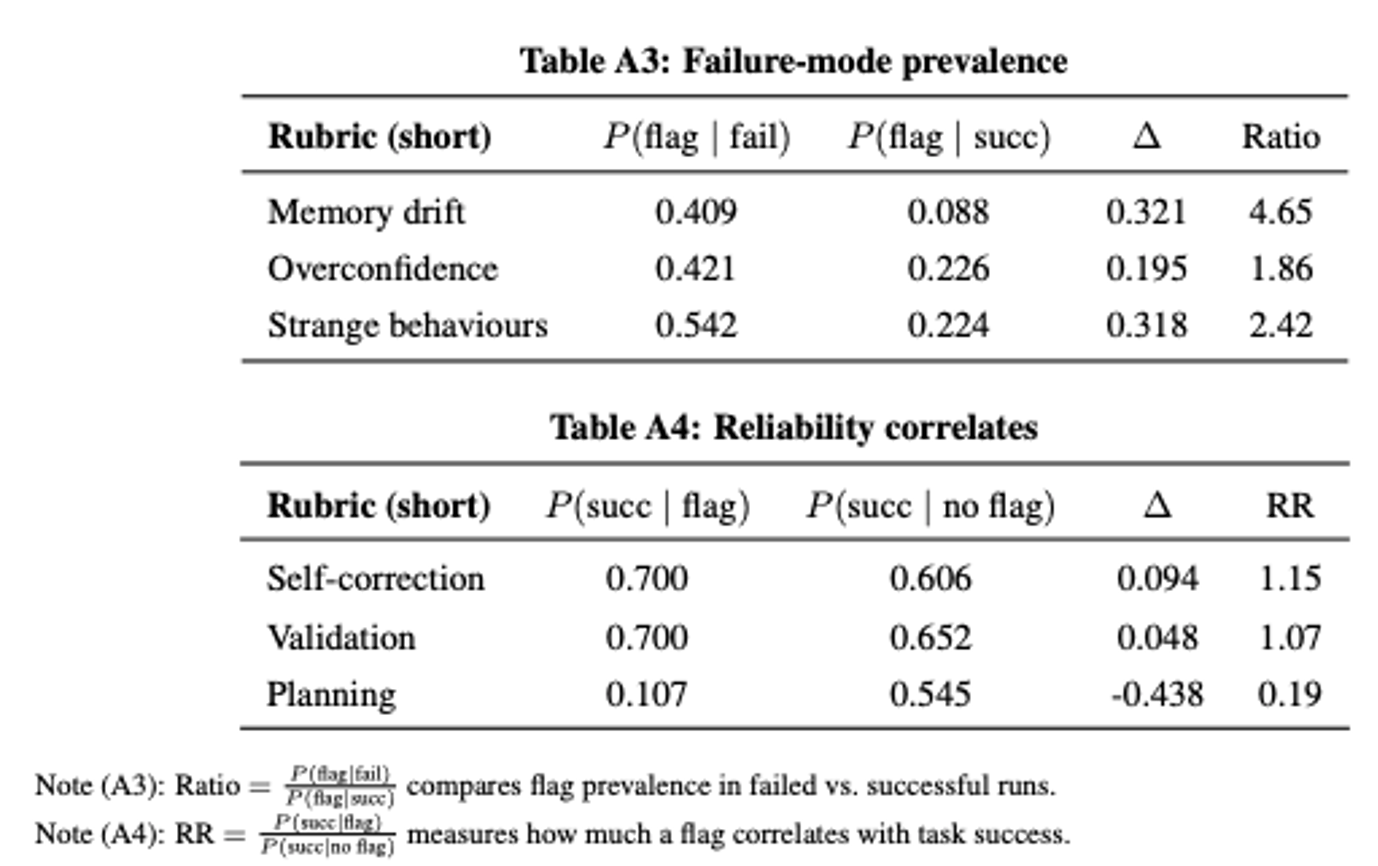

I defined a small rubric of behaviors I care about:

Failure-mode flags:

- Memory drift – forgets earlier constraints or facts from the issue / tests

- Overconfidence – declares success or final patch despite failing or unvalidated tests

- Strange behaviors – tool loops, irrelevant edits, or nonsensical actions

Reliability behaviors:

- Self-correction – explicitly recognizes its own mistake and changes strategy

- Validation – proactively runs tests or checks before declaring success

- Planning – writes out explicit multi-step plans

Each rubric item is defined as a short natural language criterion with 1–2 concrete examples to reduce LLM ambiguity.

Here’s an example rubric for memory drift:

State tracking means the agent maintains a coherent, evolving plan tied to observed tool outputs and context; memory drift means its internal model diverges from evidence, yielding contradictions, mislocalized edits, goal confusion, or misinterpretation of errors. For this rubric, “match” means the transcript contains at least one clear instance of memory drift; “no match” means no such instance is observed or there isn’t enough trajectory to assess.

Start with observability. If the transcript lacks at least two state-dependent steps (e.g., thoughts or tool uses that reference prior results), label no match and explain that evidence is insufficient to assess drift.

Check for contradictions. If the agent confidently references files/lines/symbols that aren’t present, claims success despite tool outputs showing failure, or applies edits to non-matching code snippets and persists, label match.

Check for goal drift. If the agent pursues tasks inconsistent with the repo/context after evidence shows a mismatch (e.g., keeps working on a different project or PR narrative), or treats unrelated errors as confirming the hypothesis, label match.

Check for failure to update. If repeated tool feedback (errors, search misses, failed tests) does not change the plan, leading to oscillating or inconsistent hypotheses, label match.

Account for self-correction. If issues in the prior checks occur but are promptly acknowledged and corrected within 1–2 steps and the subsequent trajectory is consistent with evidence, label no match.

If none apply. When the plan remains consistent, evidence-driven, and free of contradictions, label no match.

4.2 LLM-Judge Pipeline

For each trace, I prompt a judge model along roughly these lines:

“You are analyzing an autonomous coding agent’s trace. For each of the following behaviors, answer YES/NO if it occurs at least once in this run:

- Memory drift: …

- Overconfidence: …

- Strange behaviors: …

- Self-correction: …

- Validation: …

- Planning: …

Output JSON with boolean flags.”

Docent handles:

- Chunking long traces

- Caching / batched inference

- Writing back a normalized JSON record:

{

"task_id": "...",

"success": true,

"flags": {

"memory_drift": true,

"overconfidence": false,

"strange_behaviors": true,

"self_correction": true,

"validation": true,

"planning": false

}

}4.3 Clustering and Failure Taxonomy

Beyond boolean flags, I also cluster similar failure runs:

- Embed short LLM summaries of each failed trace.

- Run clustering (e.g., k-means / hierarchical) to group runs with similar narratives like:

- “Loops between editing and failing the same test”

- “Fixes one test but breaks others and stops early”

- “Misunderstands which file is responsible for behavior”

This gives a taxonomy of failure modes to go with the numeric metrics.

5. Quantitative Results

✅ Interpretation: Memory drift is ~4.6× more common in failed runs, making it a high-leverage failure mode to attack in the agent architecture. Self-correction and validation show positive correlations with success, while planning as currently implemented actually predicts failure, likely because the model writes long, idealized plans that it cannot faithfully execute given limited context and tool reliability.

6. What I Learned (Technically)

-

Agent performance is dominated by scaffolding design, not the model.

-

Trace-based signals convert SWE-Bench from sparse RL to trainable RL. Raw pass/fail produces a single reward per run, making RL intractably sparse. Rubric-level trace analysis produces dense behavioral labels (e.g., memory_drift, overconfidence, validation, self_correction), which act as mid-trajectory reward signals. These expose actionable levers:

- penalize behaviors like drift or unvalidated patches

- reward test-driven correction and grounded tool use

- constrain planning to short, executable steps

7. Next Steps

I’m now exploring:

-

RL-style optimization where reward is a combination of:

- SWE-Bench success

- Negative reward for memory drift / strange behavior flags

- Positive reward for self-correction and validation

-

Scaffolding search: automatically tuning DSPy program structure (module prompts, step limits, validation strength) guided by trace-level metrics.